Barbouth/Saban/Sinai

Visa Recipients

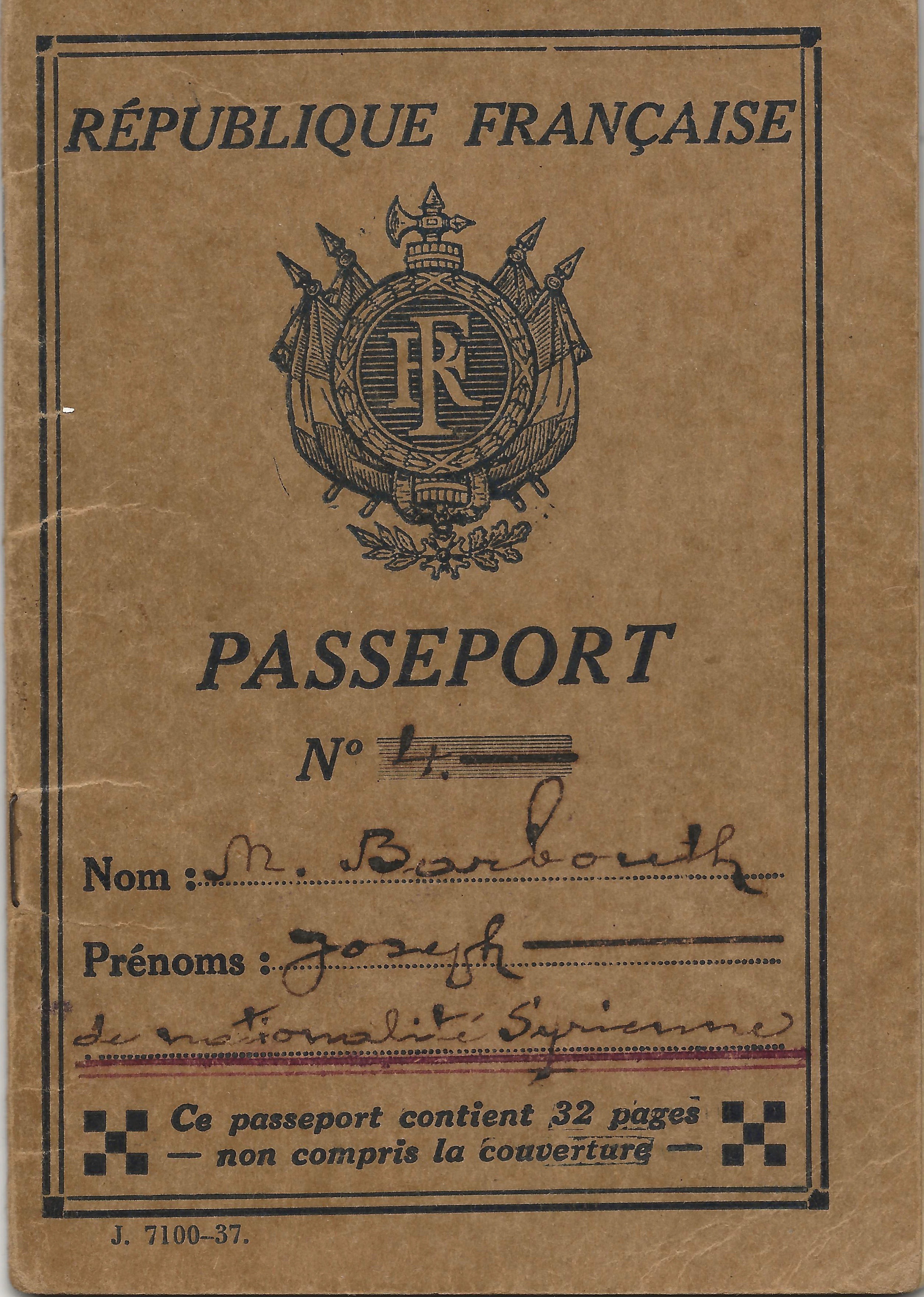

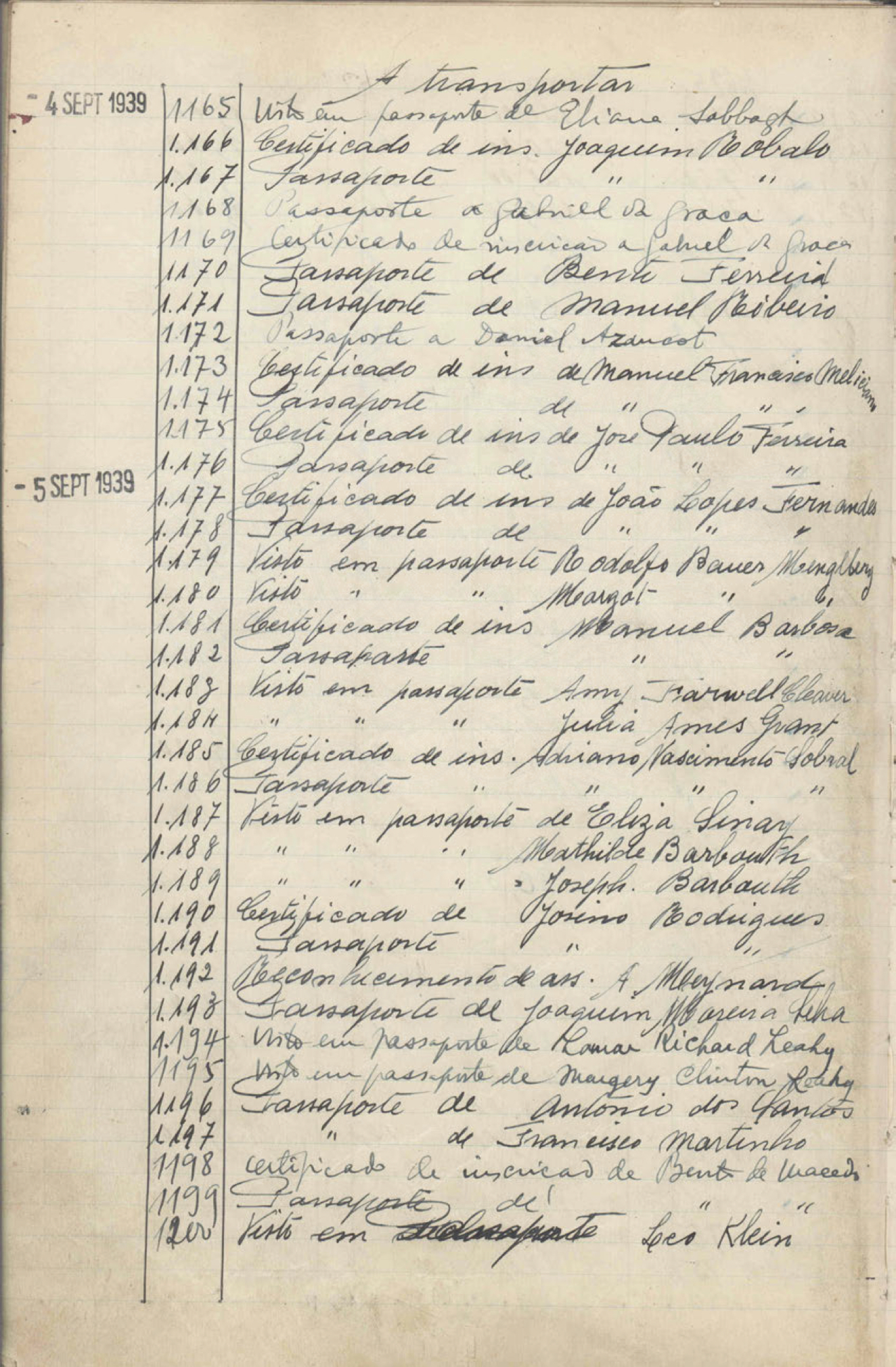

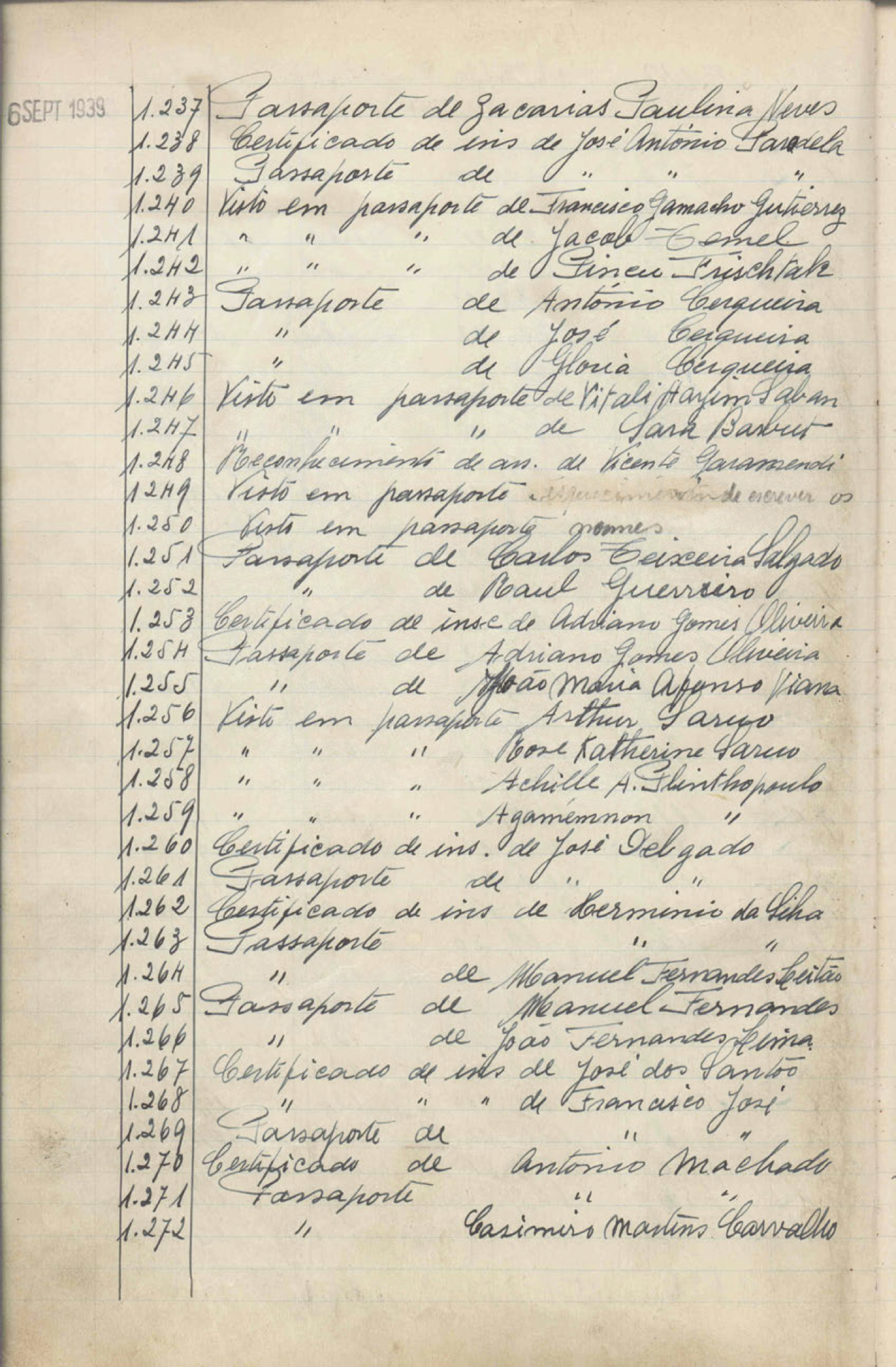

- BARBOUTH, Joseph P A T

Age 35 | Visa #1189 - BARBOUTH, Laura Sarah P A

Age 2 - BARBOUTH, Lisette P A

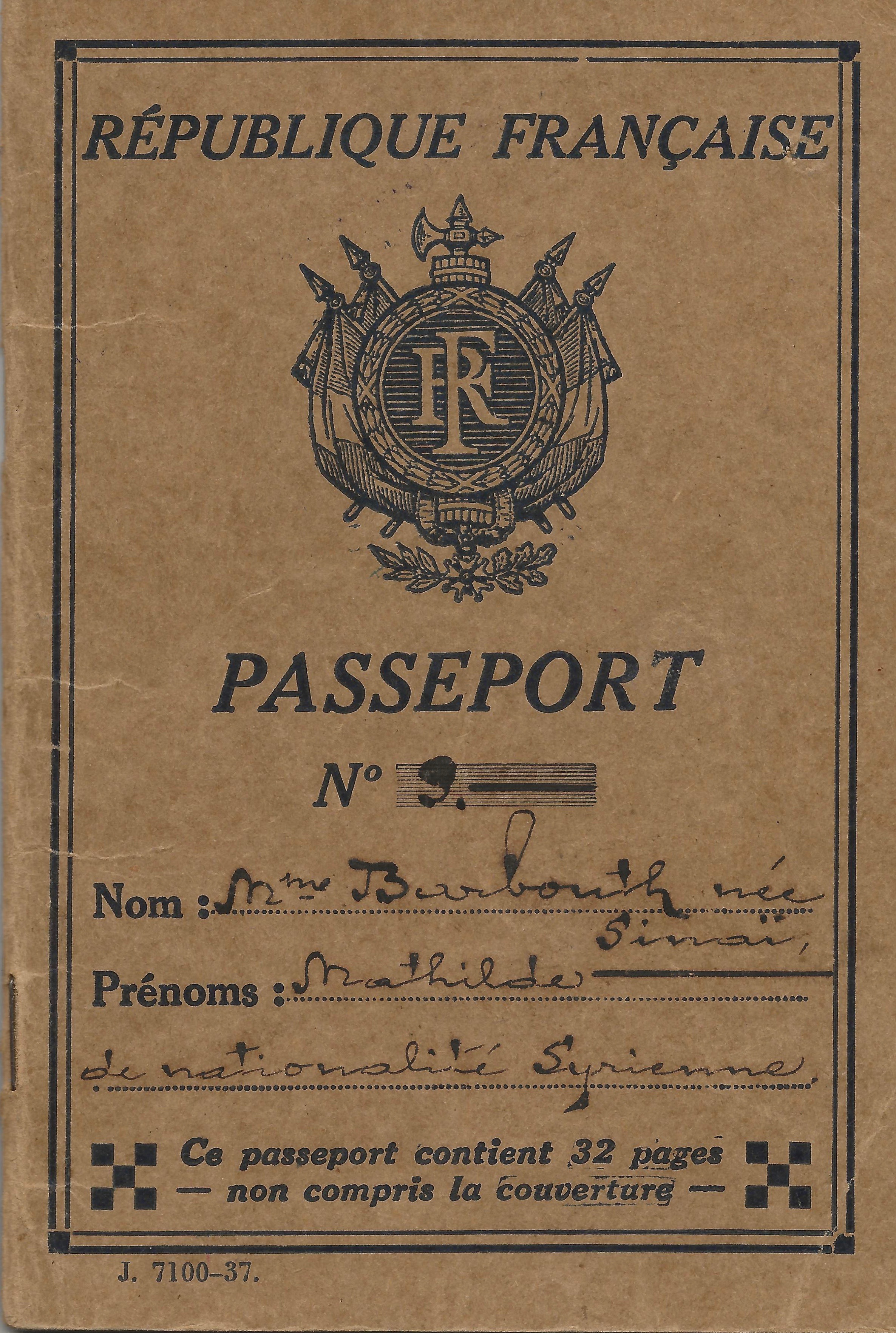

Age 1 - BARBOUTH, Mathilde née SINAI P A T

Age 32 | Visa #1188 - BARBOUTH, Sara née RODITI P

Age 53 | Visa #1247 - SABAN, Vitali Hayim P A

Age 37 | Visa #1246 - SINAI, Eliza née SARFATI P A

Age 68 | Visa #1187

About the Family

The BARBOUTH family and Eliza SINAI received visas from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on September 5, 1939.

The BARBOUTH family crossed into Portugal and from there went to Cuba in October 1939 and then to New York in May 1940. From there they went to Buenos Aires, where they settled.

Eliza SINAI travelled to Cuba with the BARBOUTH family, but remained there with her various sons and daughters who had arrived there earlier, and then moved to Canada after the war with her son Salvador and family.

Sara BARBOUTH received a visa from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on September 6, 1939. She did not use the visa to cross into Portugal but returned to to her home in Milan, where her two daughters and their families lived. She escaped though the Alps to Switzerland when Italy entered the war and returned to Milan when the war ended.

Vitali Hayim SABAN, brother-in-law to Joseph BARBOUTH, received a visa from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on September 6, 1939. He did not use the visa to cross into Portugal but returned to his home in Milan, where his wife Corinne and children lived. They moved to Argentina in early 1940.

- Photos

- Artifacts

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Carlos Barbouth, son of Joseph and Mathilde

Los Angeles, CA, May 6, 2020

Introduction

Our family’s visas were among the earliest issued by Aristides de Sousa Mendes in the very first days of the war to escape from Nazi-occupied Europe in 1939-40. That was on September 5th, 4 days after Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Actually, it came about thanks to my father Joseph Barbouth’s foresight and actions of several years earlier.

I’m taking the liberty of covering the subject with ample illustrations in this lengthy report, including the antisemitic evolution of Mussolini’s dictatorship, with the intention of providing a wide vision, from a historic perspective, of the environment and circumstances a young Jewish boy from Turkey experienced from the time he left his native country for Italy in the early 1920’s until he managed to leave Europe in 1940 with his family and arrive to his intended destination, escaping the perils he had foreseen. This is based on the documents, letters, memorabilia and complementary material I managed to obtain, keep, sort out but got to interpret only now, 80 years after the visas were issued and almost 50 years since my father’s death in Buenos Aires.

We knew about their getaway from France to Cuba and Argentina through Spain and Portugal after obtaining their Portuguese visas in Bordeaux, but our parents never mentioned the name of Consul Aristides de Sousa Mendes in particular. This was certainly because, for them, that person had been just one of the many diplomats and officials they dealt with, who were simply performing their protocolizing duties during the saga of escaping from Europe.

My parents weren’t familiar with his brave and remarkably effective actions defying dictator Salazar’s infamous restrictive orders, by supporting the many thousands of refugees needing to flee in late 1939 / early to mid-1940. His story only started to become relatively known in the 80’s, by which time both my parents had died. It was in fact through the Sousa Mendes Foundation website, and only recently, that we realized he too was part of the process that allowed our family to survive. May his memory continue to be blessed, and let his name and heroic example be widely known and repeated by others if ever needed, without any type of discrimination, given the current uncertain times for all refugees.

Retrospective

My father's father Bohor Barbouth returned seriously ill from his forced role as a senior veterinarian officer in the Turkish army after the country’s 1918 surrender in World War I, and so my father Joseph at the age of seventeen in 1922, moved from his home in Haydarpasha-Istanbul to Milan to help support the family. Joseph was sponsored by a maternal uncle named Elia Roditi, who had moved to Italy from Turkey some years before and had become a well-to-do textile businessman. Joseph's younger brother Selim Barbouth, sponsored by another uncle to go to Rumania, joined the family in Milan a year later, and their mother Sara Barbouth and sisters Corinne and Vicky moved there after Bohor died in 1926.

My father Joseph worked with his uncle Elia for many years, and in 1926, being twenty-one, he was able to obtain a Turkish passport and travelled all over the world as a textile exporter, including to Argentina, where he made arrangements that became vital during my family's European exodus in 1940.

New reality

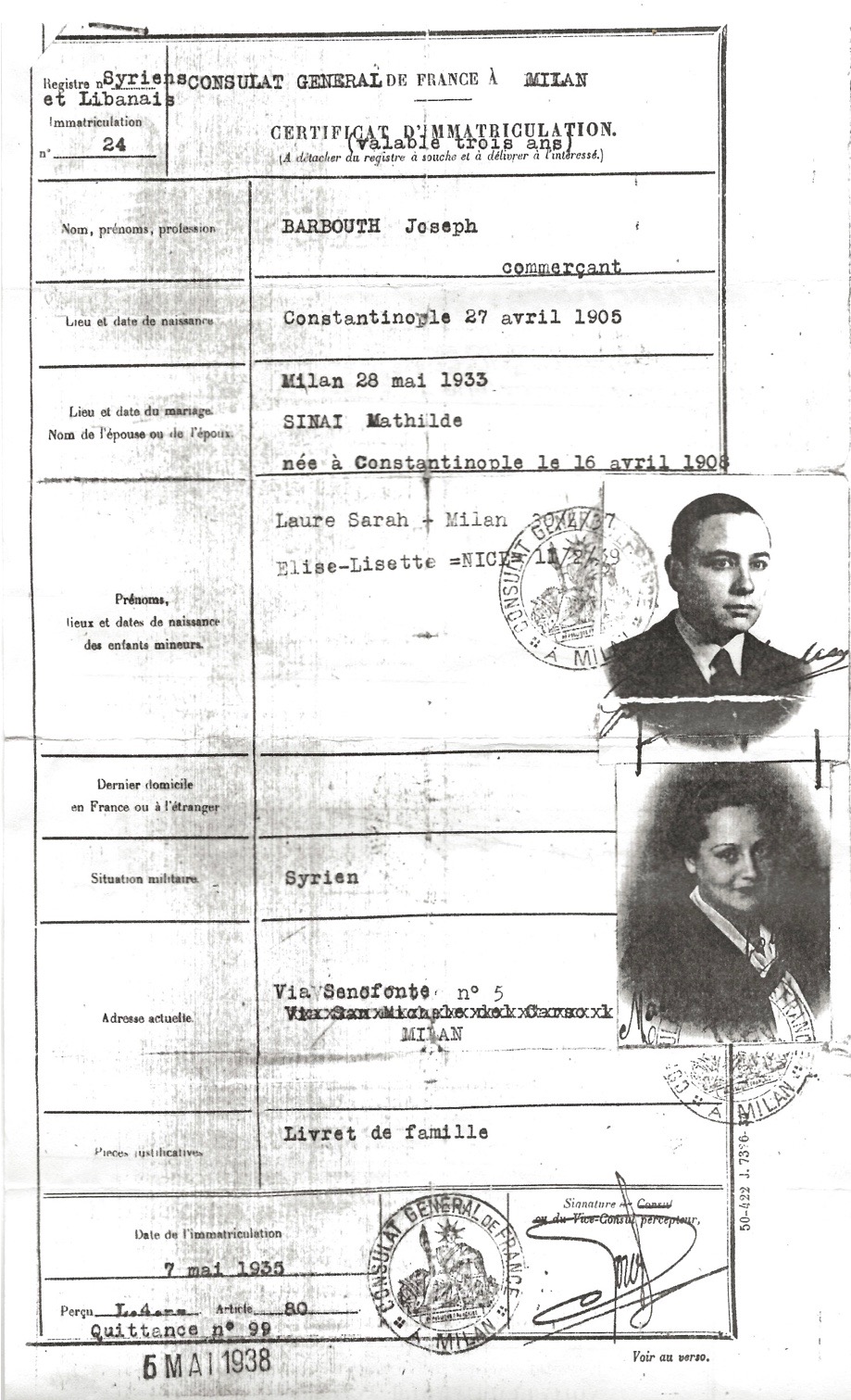

Joseph gradually became prosperous on his own, establishing various enterprises. But the Italy he had arrived to was no longer the same with Mussolini’s fascism and his imperial pretensions, which he felt foreshadowed dire consequences for the country and its people. Having married in 1933 to my mother Mathilde Sinai, two years later he decided to take protective action for himself and his wife. Being aware that France had been assigned the Mandate of Syria by the League of Nations, on May 7th 1935, he arranged to obtain for himself and my mother the formal registration as “Protégés Syriens” in the French Consulate General in Milan (see “CERTIFICAT D’IMMATRICULATION” above). These certificates were valid for three years.

With the proclamation of an “Axis” binding Italy and Germany in 1936, and things getting ever cozier between the Italian dictator and Hitler in 1937, and perceiving the probable menace for the Jews in Italy, Joseph formed a company in Alexandria, Egypt, and his younger brother Selim left Italy and moved there. Mussolini’s visit to Berlin in September that year provided a critical signal of what was coming. But it was the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938, and Hitler’s momentous visit to Rome on May 3rd that sparked my father’s decision to obtain suitable documentation in case they had to leave, because it so happened that their French certificates were expiring that very week! So on May 6th, 1938, when he was scheduled to renew them, Joseph also filed for the corresponding French passports, which included my sister Laura, who had turned 1 the previous Sunday.

All that remains of the original passports thus obtained are the photos shown above, which my father wanted to have made for just in case, and for record purposes, because they later had to be handed over and replaced. It was those passports that had the Aristides de Sousa Mendes visas.

Just two months later, in mid-July 1938, under the guidance of Mussolini’s Ministry of Popular Culture, the Manifesto della Raza (Racial Manifesto), was published, and then reprinted by the biweekly newspaper La Difesa della Razza (The Defense of Race) on August 5th.

At that point Joseph rearranged his business interests, and the family started preparing to emigrate, making whatever arrangements were possible, selling what they could and converting the proceeds into jewelry. Racist legislation intensified, but it was the subsequent Royal Law-Decrees, particularly the one of September 7th, 1938, #1381 denominated Provvedimenti nei confronti degli ebrei stranieri (Measures against foreign Jews) that made my father decide to leave Italy right away. Its article 4 stated: “Jewish foreigners who, at the date of publication of this decree-law, are in the Kingdom… and who began their stay there after 1 January 1919, must leave the territory of the Kingdom… within six months from the date of publication of this decree.”

The family rushed to finalize whatever still needed to be done, packed what they could, hid the jewelry by sewing it between the two small bottom-blankets of the fruit box on which my baby sister Laura was placed (no cribs available), and using their above-mentioned French passports, they boarded a train to France, settling in Nice.

Then came the “Munich Agreement” of late September 1938 giving Germany the Sudetenland, which some expected would maintain the peace in Europe. But that illusion ended with the German occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia in March of 1939 and the signing by Hitler and Mussolini of the Pact of Steel at the end of May. For my family, it was time to begin planning the escape from Europe should a war break out.

They decided that their initial destination of preference should be Cuba, where my mother’s brothers and sisters had already escaped to, and, when viable, ultimately to move to Argentina, where in 1930, during a prolonged business stay in Buenos Aires, my father decided to obtain an Argentine Permanent Resident Permit, just in case it could become useful some day.

But how would they get to Cuba? With Italy allied to Germany, the nearby Genoa port was out of the question, so the only reasonable way still possible would be through Portugal. Joseph's choice for obtention of the Portuguese visas was Bordeaux, because that’s where his uncle Elia Roditi and wife had moved to after Mussolini’s racial laws, and he could help out if needed, as he had done almost twenty years before when sponsoring his exit from Turkey.

In the meantime my sister Lisette was born. Thus the family now included a French-born member as well. With the situation in Europe clearly worsening, they opted to gather the remaining family members from Italy willing to leave, because since November, the Italian government’s antisemitism was in full blast.

In that context, they brought my maternal grandmother Eliza Sinai to live with them in Nice. My father obtained the Cuban immigration visas that would be required, and he arranged for his mother Sara Barbouth and his sister Corinne’s husband, Vitali Saban, to also obtain Cuban visas and be ready to cross over from Italy at short notice, to meet them in Bordeaux and get Portuguese visas as well, in case they ever needed them. Under Portuguese regulations (Circular #10 of October 28, 1938), the issuance of these 30-days visas required having an immigration visa for other countries.

Hence, when hearing of Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, my father Joseph was prepared. In less than two days they finalized whatever still needed to be done, packed up everything they could, much as they had done a year earlier in Milan, and were able to drive off from Nice on September 3rd. That very afternoon, while on their 500-odd miles drive to Bordeaux, France declared war on Germany (Britain having done it in the morning). Two days later they were in Bordeaux seeking the Portuguese visas on their French passports. My paternal grandmother Sara Sinai and uncle Vitali Saban only arrived at night, but they obtained the visas the following day.

Next came obtaining transit visas from the Consulate General of Spain, and the drive to Lisbon, crossing the Spanish and Portuguese borders without any particular incidents to mention. Once in Lisbon, my father was able to obtain tickets on the Moore-McCormack Lines’ S.S. Uruguay for their trip to Havana (as documented in the “By Ship” section of this website). Shortly after their arrival to Cuba in October, they had to go to the Légation de France in Havana to hand over their original passports and obtain new ones, as well as new French certificates, still as French “Protégés Syriens” but showing that they were now Cuban residents.

Just three days earlier, the government of the Portuguese dictator António Salazar had issued the infamous Circular #14, forbidding the issuance of Portuguese transit visas to Jews, among others, unless prior governmental approval, which in fact would not be forthcoming, had been requested and obtained in each case.

And there in Cuba my family stayed for months, during the so-called “phony war,” awaiting developments, which came with Hitler’s invasion and occupation of Denmark and Norway in April. For my father, that represented a signal of what might eventually follow, and the mere idea of remaining a French subject under a potentially German-occupied France was unthinkable. So changing their status and moving to Argentina and in due course acquiring that nationality became a priority.

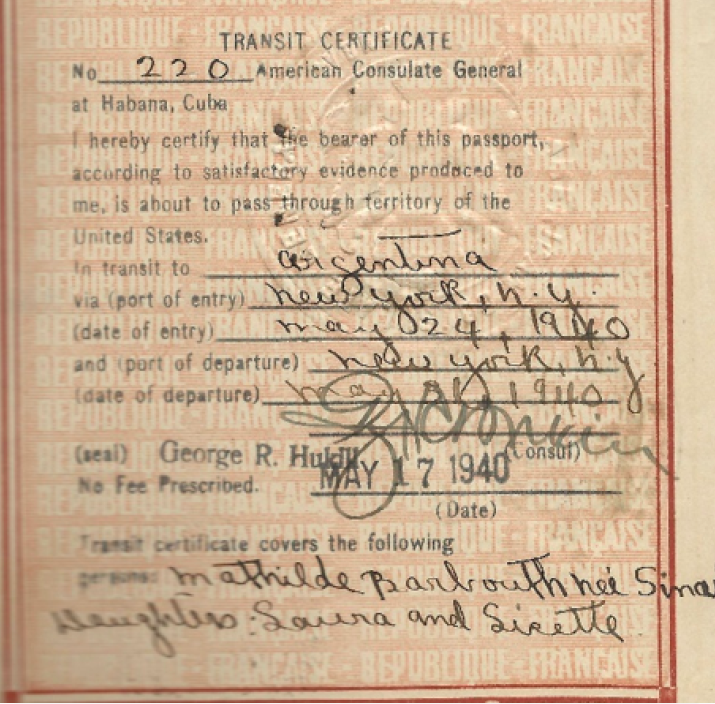

That required first the issuance of visas by the Argentine Consulate General, which was extremely restrictive when it involved Jews, as was the case in so many other countries. And then the issuance of Transit Certificates by the United States, so as to be able to embark on a ship from New York to Buenos Aires; but that required other prior steps.

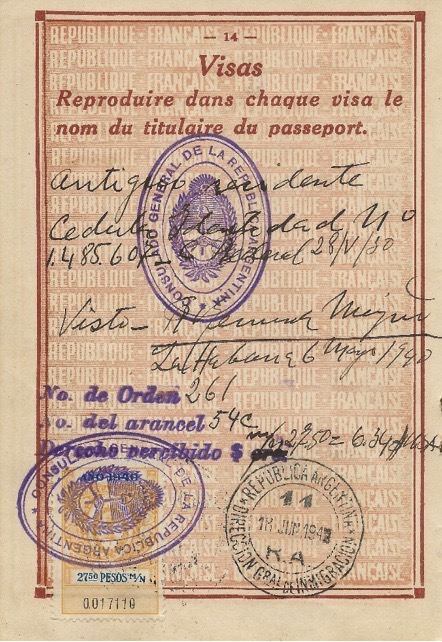

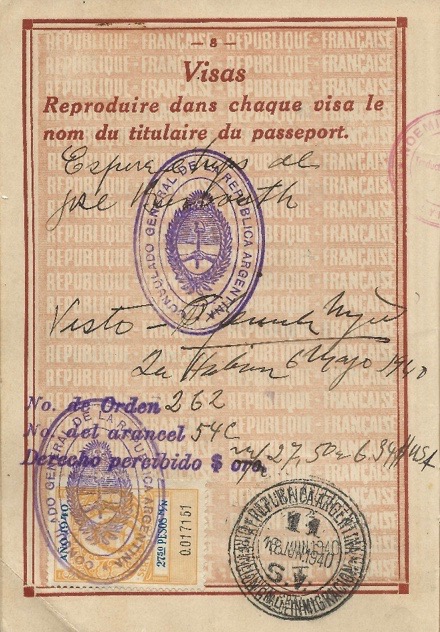

So off Joseph went to the Argentine Consulate General with the request to obtain a general entry visa, stating that he was a returning resident and presenting as evidence the “Permanent Resident Permit” he had obtained in Buenos Aires back in 1930, when he was still using his Turkish passport and had not yet become a French subject. On May 6th, the visa was granted, with the written notation that this was being done because he was a former resident (Antiguo residente), indicating the number of his Argentine Identity Card and the date it had been issued (28/V/30). At the same time he also obtained the Argentine visa for my mother, which had the specific notation that it was for the wife and daughters of Joseph, now José, Barbouth.

Next came the need of getting, at the earliest possible, ship tickets from Havana to New York, and from there to Buenos Aires, with dates of arrival and departure compatible with the United States’ requirement that Transit Certificates, which were the only permissions Jews were entitled to, indicate the exact dates and ports of entry and departure, which could not be more than seven days apart. Without tickets evidencing this, the Transit Certificates would not be granted.

So he went to the office of Moore-McCormack Lines, for the sailing schedule of their ships from New York for Buenos Aires, and he found that May 31st, 1940 on the S.S. Brazil could be a viable option. Provided they could arrive in time sailing from Havana, which he then found out they could if they took the S.S. Oriente. That liner was to set sail on May 21st and arrive to New York on May 24th. So he made the corresponding reservations for both ships, purchased the tickets, and on May 17th obtained the Transit Certificates at the American Consulate General.

In the meantime, with Germany having invaded the Low Countries on May 10th, 1940 and being on its devastating blitzkrieg towards France, moving on was ever more justified. Thus, once again, it was time to pack up and leave, this time by boarding the S.S. Oriente on May 21st (which they did, as documented in the “By Ship” section of this website).

So finally, on May 31st, they boarded the S.S. Brazil (as documented in the “By Ship” section of this website) for Buenos Aires. And it so happened that this particular trip turned out to be a historically significant one, because the immortal Maestro Arturo Toscanini, who was openly adversarial to Mussolini, also boarded the ship with the 100-piece NBC Symphony Orchestra for a concert tour of South America. They performed a concert aboard the ship, but while still aboard, it was announced that on June 10th Italy had attacked France, after Paris was declared an open city and Germany was already deep into the country. The Maestro became very upset and locked himself in his stateroom until the ship reached Rio, where he was headed. The story was widely reported in the media and became part of his biography.

After the flight of the French government from Paris and the collapse of the French army, German commanders met with French officials on June 18th, 1940 to negotiate an end to hostilities and formalize their occupation of France; and, incredibly enough, that very day my father and family disembarked in Buenos Aires. That date is shown in the seals of the Immigration authorities of Argentina on the passports’ visa pages above.

Buenos Aires, that’s where my brother Ricardo and I were born, respectively in 1943 and 1944.