Hirschfeld/Roos

Visa Recipients

- HIRSCHFELD, Alain Antoine

Age 12 - HIRSCHFELD, Blanche née BRUNSCHWIG

Age 35 - HIRSCHFELD, Charles P

Age 55 - HIRSCHFELD, Eliane

Age 14 - HIRSCHFELD, Ella née STOESSLER P

Age 46 - HIRSCHFELD, Georgette Adrienne née SAUPHAR P

Age 46 - HIRSCHFELD, Gérard T

Age 11 - HIRSCHFELD, Léopold P

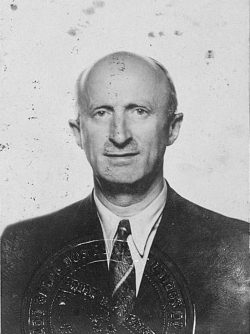

Age 65 - HIRSCHFELD, Oscar

Age 50 - HIRSCHFELD, Tony Alfred

Age 8 - ROOS, Gilbert T

Age 11 - ROOS, Käthe née HIRSCHFELD P

Age 32 - ROOS, Oscar Emile P

Age 49 - ROOS, Roger

Age 8

About the Family

This family, from Strasbourg, received Portuguese visas in Toulouse signed by Emile Gissot under the authority of Aristides de Sousa Mendes in June 1940.

They crossed into Portugal, where they resided in Lisbon. Oscar HIRSCHFELD, his wife Blanche and their children Eliane and Gérard sailed on the ship Nea Hellas from Lisbon to New York in August 1940.

The ROOS family, along with Leopold and Ella HIRSCHFELD, sailed on the vessel Angola from Lisbon to Rio in October 1940 and subsequently sailed from Rio to New York on the vessel Uruguay in February 1941.

Charles and Georgette HIRSCHFELD, along with their sons Tony and Alain, sailed on the vessel Serpa Pinto from Lisbon to Rio in October 1940 and subsequently sailed from Rio to New York on the ship Argentina in February 1941.

- Photos

- Testimonials

Testimonial of Gérard HIRSCHFELD

When we left France in June 1940, we were traveling in a caravan of four cars with three other families: the Baumanns, the Weyls (Raymond, Suzette, and two children, Phillippe and Guy) and the Blums (Arthur and his wife Alice). We traveled to Hossegor, about an hour outside of Bordeaux and spent a month there while the men were making almost daily trips to Bordeaux in an attempt to obtain visas to the United States. I was 11 years old at the time as correctly indicated in your list of recipients.

Our experience at the French/Spanish border was that we arrived one day and were told the border was closed. At that point the four men (one from each of the families traveling together) decided to go into Spain alone (without families) by climbing on foot over the Pyrenees Mountains. They would then somehow send for us from the Spanish side. When I heard this, I was terrified at the idea of being separated from my father. I have no idea how they intended to send for us since they would then be in Spain illegally and would most likely be put in jail or sent back to France, if not worse, if they tried to do anything officially. I thought I might never see my father again.

My mother vehemently objected to this "crazy" plan saying: "At times like these it's important that we all stick together rather than lose track of each other." She persuaded my father not to go with the other men who then decided not to go either. So, we all went back to Hossegor for a few days, and then, tried again. This time we had to spend the night on the floor in a hotel lobby, but the next day were allowed to proceed through the "closed" border gates in our cars after bribing the border guards. As we left France through the customs gates, this was the only time in my life that I ever saw my father cry. I still remember being quite moved and scared at seeing this man, whom as an 11-year old child, I considered quite strong and bold silently crying like a child. It was the kind of moment you never forget.

While we were traveling through Spain in our 4-car caravan, day after day in the hot early summer sun, I was riding in the front passenger seat next to my mother who was driving one of our two cars. Suddenly, I noticed the car swerving out of our lane on a two-lane road toward the other side of the road. The car was heading directly for the ditch on the side of the road. I panicked, grabbed the steering wheel and pulled it toward my side yelling MOTHER! at the same time. My mother had apparently fallen asleep on the mostly straight, hot road. The car came back into our lane and my mother brought it to a stop. Fortunately (again, thank God) we were OK, although a bit shaken. The whole caravan stopped, and everybody took a nap on the side of the road before we continued. Apparently, the other drivers felt sleepy too. No one was getting enough sleep at night in those harrowing days.

We traveled about a week until we reached the Spanish/Portuguese border (I'm not sure where that was exactly). My mother had packed a hand gun in her suitcase which my father had given her for protection when we lived in Boulogne in a rather deserted area next to the Hirschfeld Brothers factory for a few months before leaving France. She was concerned that if the border guards found the gun while searching our luggage, there might be a problem and we might be detained (or worse?). To distract the guards, my mother asked me to start playing my accordion which I had brought along. (I still have it, by the way, but have mostly forgotten how to play it.) I was very shy and hated to play in front of people, especially people I didn't know, and the custom office was very crowded. But I did play some waltzes and polkas I had learned, and people started dancing to my music. After a while, the guards joined in, and eventually, they let us through without searching anything. My accordion playing saved the day!

Since they told us there no hotel rooms available in Lisbon, we were diverted to Porto where we did find hotel rooms and spent about a month there. During that month, my parents and the other families were able to book passage to New York on the Nea Hellas, and we sailed from Lisbon on August 2, 1940, arriving in New York without incident on August 10th. I still remember huge Greek flags painted on both sides of the ship and brightly illuminated at night to signal German U-boats not to torpedo us.

As we arrived in New York, the Statue of Liberty was a beautiful and welcome sight. We later heard that on the crossing after ours, the Nea Hellas was torpedoed but not sunk, and made it safely to New York harbor. Again, thank you God for getting us safely across a U-boat infested ocean.

Our visas to the U.S. were transit visas, and we were to leave for Cuba within a week. My mother-the only one of us who spoke English in our family--went to the immigration office every week, and then, every two weeks, and then, once a month until April 1941 to request extensions and they were granted until my father's quota number came up. Then, we all had to leave the U.S. overnight and re-enter on a permanent visa as legal aliens. We went by train from New York to the Canadian border and immediately came back on legal quota numbers. After the end of the war in 1945, my father and sister went back to France. My sister and her now large family still live in Strasbourg and my mother and I became naturalized in 1946.

I'm so grateful that we were able, with the help of so many people, including Aristides de Sousa Mendes, to escape the horrors that Hitler and the Nazis inflicted on so many who were less fortunate than we were. My gratitude will never end.

Testimonial of Gilbert ROOS

Excerpt of a speech delivered on 17 November 1998

Je suis un survivant, parce que ma famille a été l'une de celles qui ont bénéficié d'un visa de transit par le Portugal... Peu importe que ce visa porte la griffe du consul de Toulouse et non celle du consul de Bordeaux que nous honorons aujourd'hui.

Je suis un survivant, parce qu'un préfet français ancien directeur du cabinet du préfet du Bas-Rhin (tous n'étaient pas des Papon, bien loin s'en faut), ce préfet à Albi nous a octroyé sans qu'il n'en ait le droit le visa de sortie nécessaire pour quitter le territoire français.

Je suis un survivant, parce que des douaniers espagnols à la Junqera et à Badajoz ont regardé de l'autre côté.

Je suis un survivant aussi parce qu'à Lisbonne, nous avons été pris en charge par une famille portugaise totalement inconnue, catholiques dévots, dont le mari -- capitaine dans l'armée portugaise -- a guidé, appuyé les démarches de mes parents, s'est porté garant de nous et je le suspecte ... a certainement aussi graissé quelques pattes administratives en notre faveur à notre insu pour nous permettre d'abord de rester à Lisbonne et ensuite de quitter l'Europe à bord d'un navire portugais avec les maigres biens que nous avions pu sauver.

Bref, je suis un survivant parce que toute une chaîne de femmes et d'hommes d'Europe ont eu le courage d'agir dans le même sens qu'Aristides de Sousa Mendes et Dimitar Peshev, qui à une époque où la vie de ceux qui étaient décrétés "Untermenschen" était sans valeur aux yeux de certains, ont appliqué avec le courage et en prenant les risques que l'on sait, la parole biblique qui veut que "qui a sauvé une vie, a sauvé l'humanité toute entière."